Last time, we learned some basic linear storytelling principles, as told to us by people that worked with books, plays, and movies. And this is fine and good for games that have a linear story. Many video games work this way, where the story is essentially told as a movie broken up into small parts, and the player has to complete each section of the game to see the next bit of movie. I do not mean this in any kind of derogative way; many popular games work like this, and many players find these games quite compelling. Even personally, I have had times when I would be messing about in the subscreens optimizing my adventuring party, only to have my wife call from across the room: “stop doing that and go fight the next boss so you can advance the plot, already!”

However, not all games are like this. As we’ve seen, player decisions are the core of what makes a game. Some games have a strong narrative intertwined with gameplay. For these games, it would make sense for player decisions to not only affect the mechanical outcome of the game, but to affect the narrative as well.

For some game designers, a true “interactive story” is something of the Holy Grail of games. In reality, we often fall short of giving the player the feeling that they are actually the starring role in a compelling story of their own creation. How have we told interactive stories in the past, and how can we make better ones in the future? It’s largely an unsolved problem, but we can at least cover the basics of what is already known, and that is our focus today.

Note that most board games do not have strong embedded narrative, so this entire discussion is mostly relevant to video game narrative, as well as tabletop RPGs. However, some modern board games are in fact attempting to combine the tabletop board game experience with that of the RPG, including story elements that the players must interact with as part of the gameplay.

Course Announcements

I will be at SIGGRAPH all next week. While I will make every effort to post on time, I may not be able to respond quickly to email and I may be slow in validating blog comments or new forum accounts, so please be patient. Naturally, if you are attending there yourself, feel free to say hello in person – I’ll be speaking on Monday morning about the results of the Global Game Jam.

Readings

Read the following:

- A Point of View, by Noah Falstein. We talk of the point of view of a story as “first person” or “third person” – and we also talk of the point of view of a video game in similar terms (First Person shooter, Third Person stealth, etc.). It is easy to assume that the two are equivalent, but they are not. This article makes the differences clear.

- Diversity in Game Narrative, by Chris Bateman. This is a brief overview of the different kinds of story structures encountered in games.

- Challenges for Game Designers, Chapter 13 (Designing a Game to Tell a Story). This short chapter covers today’s topic and can also serve as a review of some topics from last time.

Kinds of Stories

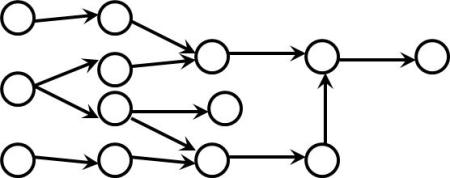

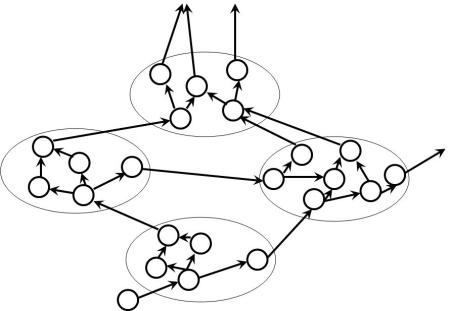

We can roughly classify different stories by their overall structure. The structure is determined by what kinds of choices are available to the player, how open or constrained those choices are, and what effect those choices have on both the ongoing story and the final ending. Each structure has its advantages and disadvantages, which we will discuss below.

![]()

Linear

Linear stories are the traditional narrative, with some gameplay elements thrown in that do not affect the story. In this case, the story and gameplay must be separate entities, because the story has no choices and the gameplay must include decision-making of some kind (else it is just a story and not a game). They can be thematically linked, and the story may influence gameplay (perhaps when a certain pre-scripted story element happens, it causes a new gameplay effect to come into play), but the gameplay cannot influence the story because there is only one story.

Linear stories have one major advantage over all other story structures: it is easy to apply traditional storytelling techniques, which have been developed over thousands of years. Such a story can have a powerful emotional impact – witness that we still talk of Floyd’s death in Planetfall and Aerith’s death in Final Fantasy 7 as key moments in the history of game narrative… even though neither events was under player control.

Linear stories have the obvious disadvantage that, due to a lack of decisions, they are not very game-like. As stated above, there is a natural barrier between linear stories and game mechanics, which limits the effect the story can have.

Branching

The first and most obvious thing to do to a linear story, if we want to add decisions, is to add choice points at various places. When the player reaches a certain point, they decide what to do, and then the story goes down one of several continuing paths until another choice point is reached. An example is the old-school Phantasy Star III for Sega Genesis; twice in the game, the main character is given a choice of which of two girls to marry (and then the story continues to the next generation of characters), leading to a total of four branches, each with its own story and its own ending.

Branching stories have the advantage of being interactive. If you include a sufficiently large number of choices and your choices cover all of the things that a player would want to do, the game can respond believably to any number of player decisions. At first, this would appear to be the ultimate solution to game narrative since it can handle just about anything.

However, there is one major drawback of using a branching story: it is expensive! With only two choices (which is not very many), the story writers of Phantasy Star III still needed to write four stories. A third choice would have had them writing eight stories, and including a mere ten choices would require writing 1024 stories! Consider the number of decisions you make as a player in a typical strategy game, and you’ll see that the amount of work to write a branching story can quickly explode into something unmanageable.

To make things worse, note that a player that goes through the game once will never even see the vast majority of content. It requires multiple replays just to see every path through the story… and even then, the player must decide which is the “real” story and which are the alternate timelines that didn’t actually happen. (If the developers ever make a sequel to the game, they must deal with this problem as well.)

Parallel Paths

This is Bateman’s word for a branching story that collapses in on itself, allowing the player to make choices but then collapsing all of them eventually into several mandatory events. In Silent Hill, for example, there are several choices the player can make that may advance the story or reveal some additional story elements along the way, and these will influence the ending. However, there are certain events that the player is forced to encounter no matter what else they have or haven’t done.

Parallel paths solve the problem of branching narrative by keeping the advantage of player decisions while still keeping the total amount of story manageable. So, at first, this would appear to be the ultimate story structure.

As you might guess, there is still a problem: since the player is forced into certain events, the entire plot arc is now essentially linear again. We have lost the player’s feeling that they are directing the story, because no matter what they do there will be certain parts of the story that are the same no matter what.

One potential solution is to have the player decisions alter the game’s ending. The player may still encounter the same plot arc, but the final outcome is determined by the choices the player made. Unfortunately, that means the relationship between cause and effect can be easily lost – the player’s decisions are (by definition) not seen until the very end, and it is often unclear what the player did to cause a certain ending.

And, we still have the problem that the player must replay through the entire game multiple times just to see all the endings.

Threaded

This is Bateman’s term to describe stories that are divided into small pieces, perhaps with several plot arcs going on at once that may or may not intersect. The player then chooses which paths to follow and in what order. One example of this is World of Warcraft, where the player can accept any of several quests to advance different elements of the story. Another example are the Elder Scrolls series of games (like Morrowind and Oblivion), where the player may follow certain storylines based on how they want to advance their character, and the player may find other quests or subplots that they choose to pursue (or not) along the way, and these subplots may or may not have their own effects on the main plot line.

The advantage of a threaded narrative is that it is extremely expressive. You can have multiple storylines happening concurrently, as with nonlinear films like Pulp Fiction or Love, Actually (except, unlike those movies, have the plot lines advance according to player intent).

Also, the story may have multiple beginnings and middles and endings, but the player has access to all of them and can advance any combination of them in any order, so we have finally solved the problem of forced replays. The player can see everything there is to see with a single play-through, if they are thorough enough.

As you might guess, there is still a problem here. First, since some events may affect others, testing out all possible paths through the story can get even more complicated than with a branching narrative. (For programming geeks, a branching story with two choices per choice point is O(N^2), while a threaded narrative is potentially O(N!). Yes, factorial.)

Writing a threaded narrative is hard, because events can happen in any order, leading to the potential for the player to do things in an order that doesn’t make sense (for example, perhaps they are given a quest to assassinate a rival leader in the middle of a war, before the war actually breaks out, or after the war is concluded). The story writer must be careful to allow access to certain story events only when it would make sense to do so. Keeping track of all the variables that determine when a story event is or isn’t active can get very complicated very quickly.

Lastly, a threaded narrative runs the risk of confusing the player, if there are too many concurrent plots happening at a single time and the player does not immediately see the relationships between them. This is also a danger with books and movies that try to tell several stories at once.

Dynamic Object-Oriented Narrative

This last structure is Bateman’s term that, as far as I can tell, he invented to describe the game Façade (which you should absolutely download and play if you have not yet seen it). The idea is that there are several mini-stories, each with potentially several entry points and exit points. A single mini-story’s exit point may lead to a final ending, or to another mini-story. The mini-stories may be thought of as “chapters” in a book or “acts” in a play (except that you may not “read” all of the chapters or may read them in a different order, depending on the choices you make and how you exit each chapter).

This kind of story has the advantages of parallel paths, but without a linear story arc. Each mini-story has its own choices, and the overall collection of mini-stories itself acts like a larger branching or parallel path story. Each individual mini-story is self-contained, which reduces the required time to write the complete story.

This kind of story has two disadvantages. The first is that there’s still the forced-replay problem: a player must play many times to see all of the story paths (which is perhaps why Façade needs to last about ten or twenty minutes, and not ten or twenty hours). It is also a highly experimental structure, so we do not yet have enough games to really analyze what does and doesn’t work in this form. Façade itself took a couple of guys with PhDs in Computer Science to develop, so this is not the kind of story structure that is easily accessible to a traditional story writer.

Points of View

The camera in video games is generally either first-person or third-person.

Camera Views

A first-person view means the camera is, essentially, glued to the main character’s forehead looking forward. The player sees what the character sees. This can lead to a greater sense of connection with the main character, because the player is inside the character’s head, so to speak. The disadvantage is that this is not truly a first-person view, because a typical human’s peripheral vision is wider than the screen (and a typical human can turn their head faster than a typical first-person video game camera), which can break immersion at times for players who are not used to the limitations.

In a third-person camera view, the player is instead looking at the main character, usually from a behind-the-shoulder perspective so that you usually see the character’s backside. This gives a wider view of the area and is more realistic in terms of giving the player the visual information that the character would have. Of course, by looking at the main character all the time, it brings a sense of otherness – you can’t look at your own backside without the aid of mirrors, so this camera view is a reminder that the main character is not you.

Combining this with McCloud’s point on icons versus realism (from last time), we might guess that a first-person character is closer to an icon and tends to do better as a “blank slate” character that the player can project their own personality onto, while a third-person character that is drawn realistically should have strong characterization.

A second-person camera view, if it existed, would involve the camera that spends the entire time looking at the main character from the front. Needless to say, this would be confusing in the vast majority of games. The closest I’ve seen is an obscure console title, Robot Alchemic Drive, where you control a human character (in third person) that is in turn controlling a giant robot by remote control (in second person). To the extent that the robot is the main character, this game uses a second-person camera for control.

Story Views

We also use the words “first person” and “third person” when discussing literature. There, it works a bit differently.

A first-person story is when the story is told from the narrator’s own point of view. The main character is addressing the reader directly, telling you a story of what happened to them.

A third-person story, which is more common, is when the story is told from an outside perspective (much like a typical movie camera, where the view just represents a “fly on the wall” and not an actual character’s viewpoint). This may be “third-person omniscient” where the reader can see things that happen and even hear several characters’ thoughts, or “third-person limited” where some information (such as character thoughts) is concealed from the reader.

A rare kind of story in literature is that of second-person, where the story is told from the reader’s point of view. This kind of story is rare because it is very hard to write in a way that is believable.

You might be realizing about this time that almost every game narrative is told in second person. This is the case whenever the player is controlling the main character, which is most of the time.

And this is another reason why storytelling in games is so hard.

Interactive Characters

Sometimes, the overall plot arc of the game is fixed and linear, but there are a number of characters (specifically, “non-player characters,” referred to as NPCs) that the player can interact with. In video games, where interpersonal relationships must be quantified, there are two common ways to treat NPCs and their relations with the player.

Flags

A “flag” in this context is just a binary (yes-or-no) value. An action did or did not happen. The player did or did not talk to a certain NPC, and if they did, they either did or did not choose a particular conversation path. As a result, certain new NPCs or conversation options may appear or disappear.

The advantage of flags is that it is very simple to do. Everything either happens or it doesn’t, making the logic that drives the characters pretty easy to follow. It’s also easy to implement in code; programmers can do binary logic easily.

The disadvantage is that there is not a lot of depth to these characters, if there is only black and white and no shades of gray in between. You can add more complexity by combining binary values (“only make Aragorn appear if Frodo chose to travel to the Prancing Pony and he successfully avoided capture by the Ringwraith and he puts on the Ring”) but at this point it can get complex to follow, reducing the benefit of simplicity mentioned earlier.

Affinity

Instead of a yes/no dichotomy, use numeric values to measure things like how strongly a character feels affection or hatred towards another character. If you have to decide whether an NPC behaves in a certain way, check to see if its affinity value is past a certain threshold value. (In tabletop RPGs, it is common to also add a die-roll to the mix, so that things may or may not happen based partly on chance.)

The advantage of an affinity system is that it is still fairly simple, it can handle more complexity than a flag system, and it is much more expressive.

However, you must be careful with affinity systems. There is a danger of having a very muddy system (where the player can’t tell why a character behaved in a certain way), especially if several affinity variables or a random die-roll are included in determining the outcome. In short, it is hard to get this kind of system to “feel right” without a lot of playtesting.

Character Conversations

Some games include a conversation system, where the player is given a choice of things to say, and then the NPC they’re talking to responds.

Conversation systems can be thought of in the same way as game narrative systems. A conversation can be:

- Linear. I walk up to an NPC and choose the “Talk” command. They tell me something. That is all.

- Branching. I initiate a conversation. The NPC says something, and I am then given a choice of responses. Based on my response, the NPC may say something else and then give me a brand new set of responses.

- Parallel. I initiate a conversation. The NPC says something, and I am given a choice of responses, then they respond, and so on. There are several combinations of responses that can get me to the same outcomes, however.

- Threaded. I initiate a conversation, and am given a set of different ways to begin. The NPC responds to what I say, and each action I take within the conversation may open up new paths of conversation and close older, no-longer relevant conversation threads.

- Dynamic. I go through a branching or parallel conversation. Depending on the outcome, I proceed to a new conversation (or a new area of exploration within the current conversation).

Writing dialogue in each of these methods is proportional in difficulty to writing a story of each form.

Writing Good Characters

Some characters in stories are “round” – they have many facets to them, a deep character with many layers, and are highly detailed and developed over the course of the story.

Other characters are “flat” (or “shallow”) – they are very simple, don’t have a very deep personality (at least, not that the audience can see), and do not develop or change much (if at all).

Normally if we say a character is “flat” it sounds a bit derogatory. Are flat characters always bad in stories? I don’t think so; not all characters need to be complicated, deep, or well-defined. Even in Shakespearean plays, some minor characters are flat (I’m looking at you, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern), but the main protagonist and villain at least should be round.

A rule of thumb is that a character should develop over time as we seen them through the story. As a corollary, minor characters with very little “screen time” can be flat since they don’t have much time to develop anyway; the characters who we see the most often (generally the main characters) should develop a great deal. A flat protagonist is probably not a good idea if you are trying to make a strong character.

Archetypes versus Stereotypes

Here’s a question I was once asked in a job interview: describe the terms “archetype” and “stereotype” and the difference between them.

McKee says that story is about forms, not formulas. Archetypes are forms; stereotypes are formulas.

“Villain” is an archetype. The Snidely Whiplash-esque, mustache-twirling, top-hat-and-black-cape-wearing, purely-mean-for-its-own-sake bad guy is a stereotype.

Archetypes are useful. They allow us to tell a story with believable characters that fit familiar forms. Stereotypes are overused, and typically make a story less believable because the audience has seen these same characters before from other stories, so they do not seem unique. Generally, avoid stereotypes, unless there is very good reason (such as if your story is a parody that is making fun of a particular character stereotype).

Freytag’s Triangle

You might have seen this before in a grade school literature class. The idea is that stories start with a small amount of exposition to set the tone, then they have rising action where things get more intense, then they reach some kind of climax (a final battle or confrontation, etc.), then there is falling action and resolution at the end as the story reaches its conclusion.

Note that this is not just true for story, but for gameplay as well. Games have exposition (we call it the “opening cinematic” and “tutorial level”), rising action (most of the game), climax (final boss fight), falling action (occasionally some post-fight sequence like a timed escape from the building before it blows up), and resolution (end cinematic).

You get a more dramatic experience if the dramatic arcs of story and gameplay are aligned and in synch with each other. This is a lot harder than it first appears; in many games, the most difficult part of gameplay occurs somewhere in the middle of the game, when the enemies and challenges are getting harder but you haven’t yet found new weapons and abilities to power yourself up to compensate. As the player gets more powerful and better at playing, the challenge of a game often decreases over time, even as the intensity of the story is increasing. You can tell these games when the final boss fight is introduced with this high amount of drama and foreboding, and then the player wins after swinging their sword around for a few seconds – it feels anticlimactic and not very believable.

In short, as you balance your game, pay attention to the story and whether the story drama is proportional to the dramatic moments in gameplay.

It’s Still a Game

Remember that, as a game designer, you are still making a game and not a story. In most cases, the story should not preclude gameplay. At the very least, you should be extremely careful when you are tempted to make a concession in gameplay for the sake of the story, or when you plan to overload the player with non-interactive story bits.

When writing the narrative for a game, return frequently to your core aesthetic – your overall vision of the optimal experience your game will offer – and make sure that the story supports it!

Lessons Learned

There are lots of ways to take a traditional linear story and make it more interactive. All of these have advantages and drawbacks. If the Holy Grail of a full interactive story is even achievable, we have still not discovered how.

But we should keep trying, and exploring the various non-linear story forms that are uniquely suited to games.

Reading

If you have time, before beginning the Homeplay below, please take the time to read at least five other posts at your skill level from the Pente challenge from Level 9 (posted on the forum), and also at least five other posts at a skill level above yours (unless you posted in Black Diamond). Do this on or before Monday, August 3, noon GMT.

As you read, pay attention to the variety of responses you see. Do you see any recurring themes, or are people’s experiences different from each other? Why do you think that is? Reflect on this.

Midterm Review

You get a break this weekend: no homeplay. If this were taught in a classroom, you would have a take-home midterm exam at this time. But I do not have the time or the desire to grade 1400 exams, nor to generate a series of unique questions. Instead, I provide this brief review of what we have covered. Next Monday, we will transition from the mostly-theoretical discussions on what makes compelling games, to the mostly-practical business of actually designing an original non-digital game from scratch and taking it through the process from concept to completion.

We have come a long way in only five weeks, and for those of you who have kept up, I salute you. We’ve covered most of the basics of how to design a game. In particular, we have discussed:

- The importance of having a critical vocabulary to discuss games, along with the acknowledgement that we do not have one that is strongly developed yet.

- There are many definitions of the word “game”… but they are generally too broad, too narrow, or both. Most games include rules, goals, conflict, decision-making, the “Magic Circle,” a lack of net material gain, and an uncertain outcome. Most games are activities, they are voluntary, they are make believe, they are closed systems, they are representations or simulations, and they are a form of art.

- Player intentionality (the ability of the player to form a plan and carry it out through the game’s systems) requires clear feedback, and competes with linear narrative.

- There are many formal elements of games: players, goals, rules, resources, and so on. Each element must be intentionally designed, and it is also useful to start with the formal elements when analyzing an existing game.

- Games are systems. They must be set in motion (i.e. played and experienced) to be fully understood.

- Games require rules for setup, progression of play, and resolution.

- Mechanics are the rules of play. When set in motion during play, these lead to the Dynamics, or the actual play of the game. The dynamics have a mental and emotional impact on the players, or the Aesthetics of the game. Designers create the Mechanics only, designing from the “inside out”; players experience the Aesthetics first, learning the game from the “outside in.”

- Most games have a single strong core, the gameplay experience that is fun or engaging or meaningful or whatever the overall vision is. When designing the game, return to this core vision constantly and ask if all of the mechanics support the core.

- Emergence is a special kind of dynamic that is experienced as complexity that arises from the interaction of relatively simple dynamics. This can be useful in that the mechanics are what must be designed (and programmed, in the case of video games) so it can ostensibly deliver a deep gameplay experience for relatively little effort. In reality, much of the cost is simply shifted to playtesting, as emergence is not always a positive effect on gameplay, so it must be tested heavily.

- Feedback loops are another special kind of dynamic. Positive feedback destabilizes the game by causing the winners to win faster and the losers to lose faster in a “snowball” effect. Negative feedback stabilizes the game by disadvantaging the winners and providing extra help to the losers. Feedback loops are not always desired or intentional, though they do have their uses; designers must be sensitive to detecting feedback loops and deciding whether they are good or bad for the game.

- There are many different kinds of fun. There are also many systems that define player types. Designers create fun, not players, so “player types” are mainly useful in understanding the kinds of experiences we must create. Many things that we find “fun” can be traced directly to our distant ancestors and the skills they needed to survive.

- There are many kinds of decisions players can make in games. Meaningless decisions have no effect on the game’s outcome. Blind decisions have an effect, but give the player no information on which to base their choice, so any decision is as good as any other. Obvious decisions have an effect, and offer too much information, so that one decision is clearly better than all the others. More interesting decisions involve some kind of tradeoff, where the player gains one thing but loses another.

- When people enter a deep state of concentration, it is called being “in the flow.” One way to achieve this state is by being challenged by a task that is not too easy but also not too hard. It is a pleasurable state to be in, and games are particularly good at putting their players in a flow state. Flow is pleasurable because the player is learning a new skill (or strengthening an existing skill).

- When writing linear stories, we can learn a lot from the last couple of centuries. Aristotle tells us that stories should be a believable chain of causes and effects brought about by the main character, and that stories should have a beginning, middle and end. McKee tells us that story is about forms, that story is about change, and that character is more important than characterization. Campbell gives us the Hero’s Journey story form, which is useful when writing stories about heros.

- There are several different non-linear story structures that allow for player choices to influence the story. They all have advantages and disadvantages.

Have a restful weekend, and I’ll see you back here on Monday, August 3 at noon GMT.

July 30, 2009 at 4:02 pm |

Just for reference … there are some good ideas on character conversation (and the purpose of NPCs in games) here:

http://emshort.wordpress.com/writing-if/my-articles/conversation

This is in the context of Interactive Fiction (ie. parser-based text adventure games).

The author (Emily Short) is working on a threaded conversation system, which she is writing a series of articles about. The most recent one is:

http://emshort.wordpress.com/2009/07/30/modeling-conversation-flow-npc-repeating-information

July 30, 2009 at 10:26 pm |

Thank you, Ian. I appreciate and am really grateful of the effort you have put into this course; I have also been trying to do my part to get as much from it as I can. So far I have been challenged, and have learned many a thing, so even if I were to quit now, it’s already been very worthwhile. But I don’t plan on doing that, of course!

July 31, 2009 at 9:46 am |

this is my favourite lesson so far. It goes through so many fields.

July 31, 2009 at 11:24 am |

I don’t see the “forced-replay problem” as a problem at all; In fact, it seems to me that it is exactly equivalent to the player being able to make decisions that actually affect the story. If the player makes an actual choice in the story, then there’s always at least one other option that he did not take.

(the threaded story type only seems to get around this if each thread is linear, making it sort of like playing several linear games in one world…)

I think this is only a problem when you look at story from the “old” linear, static perspective: In that case, you feel like you are missing something (lots of something) if you don’t access every bit of what the author put in there.

But if you think of story as more of a dynamic system thing, you don’t need to explore every last bit of it to get the idea it’s trying to get across…

I think (well, hope at least) that the sort of dynamic, systematic stories like the one in facade are the future of game stories, and what will really differentiate game stories from books and movies.

(also, if the story is more like a system than a static tree, then testing out every single possibility is not only infeasible, but unnecessary – after all, when you’re testing a physics game, you don’t manually test every single position and speed an object could have and whether that breaks the game… )

July 31, 2009 at 1:58 pm |

Well Yana, one of the main complaints about narrative systems that require multiple playthroughs to see everything comes from the people who have to make or fund all the content players aren’t seeing in a single playthrough.

They argue that many players won’t take the time to play through multiple times to explore more of the content, so why should they build/provide-funding-for all that extra content? That only a small percentile of the players are actually going to see?

There are certainly many players who like to do multiple playthroughs and explore other options — I’m one of them if I can afford the time. But I can also definitely sympathize with the players who beat a game once and decide to set it aside and call it ‘done’. There’s plenty more games on their pile to get through…

August 2, 2009 at 12:43 pm |

Had the pleasure of listening to R. Bartle (Inventer of the MUD and referred to in earlier lessons) talking about the Hero’s Journey, but his spin was that the Hero was the player, the mythic wood was the game, the world returned to was ours, etc. for example, an addiction to World of Warcraft was a refusal to return to the world. His thesis was that games without end – i.e. MMOs – are only completed when you STOP playing and walk away. Was absolutely fascinating. Afterwards, at the pub eating and drinking with him, it was proposed that the Hero’s Journey might not be a suitable to generate the “in game” character story, but was an excellent template for the human playing!

August 2, 2009 at 10:21 pm |

Why fund something that only a small percentile of players will see? Because if you can really touch that small percentile then you’ve actually accomplished something. If you make it so lots of people see it and none are touched by it, then it’s a one hundred percent waste. Or in other words, the efficiency problem is a misnomer, because if you sacrifice meaning to reduce play through then you’ve reduced yourself to 0% efficiency and wasted ALL of your writing.

Rather a better way to proceed, in my opinion, would be to make each choice meaningful to whatever percentage chooses it. That way although a small percentage sees it, all of the various small percentages equate to a large majority of satisfied costumers. We are still fundamentally designers and engineers. Our job is to make templates and prototypes not to be mass producers, so the measure of our work is it’s quality, not it’s quantity.

August 3, 2009 at 10:17 am |

Gamebook fans often talk about ‘replayability’ as a desirable trait of gamebooks. ‘Replayability’ means that you can read the book once you’ve beat it and it’s still challenging and/or interesting. This might be because there are different character possibilities with different ways of winning, or it might be because there’s more than one way of winning and you can try to discover a new one.

So in that context the ‘forced-replay problem’ is considered a good thing.

August 3, 2009 at 11:08 am |

Narrative discussion in games is a very rich subject and as discussed earlier in the post part of it has to do with the fact that we can be just as happy with linear narrative as we do with something else. It’s really up to the player (and there are many types) and the compelling game play that is presented.

I feel as if we’ve had great advances in narrative with the sheer amount of content. MMO’s are still a mystery to me since I can devote very little time to playing games I am hesitant to dabble. Mike Reddy’s earlier comment makes me wonder what type of patterns seem to emerge from this very complex genre of games.

August 4, 2009 at 12:12 am |

Sorry for the delay, but I wanted to let you know that I tried making a second-person camera system once. Once.

One version of the story is here: http://blog.theschoon.com/second-person-perspective-in-games/

Either way, the conclusion is that it didn’t work well at all, but I loved the thought experiment as a game developer.

February 8, 2010 at 3:04 am |

just want to ask you something like always =]

do you think story has no place in a sandbox style game like gta or zelda?

i mean from my experience the story didnt have that much of an impact because it cannot be properly paced. for example hyrule is being destroyed by gannon and princess zelda is trapped and in the meantime im fishing for 5 hour..

February 8, 2010 at 5:34 pm |

Hi Jason,

Great question! It occurs to me that in both lesson 9 and 10, I neglected to say anything about whether there are times when story is inappropriate, or when there should be less or more of a focus on the embedded narrative of a game. After all, Tetris doesn’t need a story (and the story that was added in Tetris Worlds was… um… well, let’s just say that it didn’t exactly make me feel like part of a larger world… fine game otherwise, though). On the other hand, Final Fantasy without a story would kind of fall flat. So what’s the deal?

I think the answer is that the amount of story should be a deliberate design decision, but that there is no “wrong answer” per se. The earliest First-Person Shooters didn’t have much of a story (other than “you’re a guy with a gun, those things over there are monsters, GO!”)… and that was fine for them… but then Half-Life came along and showed that it is in fact possible to have an actual storyline within an FPS, and that was fine too.

With Zelda as an example, you’re right that this game doesn’t exactly have a huge storyline: bad guy appears, good guy goes through a series of dungeons leading up to a final confrontation, the end. Classic Hero’s Journey in a paragraph, right? But then, that doesn’t mean that a “Zelda-like” game (ARE there any Zelda-like games other than Zelda these days?) could not focus on having a strong story element in the same way that Half-Life did.

As for a sandbox game like GTA, typically those *do* have a main storyline… it’s just that because of the sandbox nature of the game, the player can choose to either follow the story or ignore it. GTA itself, I believe, tends to have a single linear storyline with maybe a few optional side plots. A game like Oblivion, on the other hand, might have one main plotline but with several ways to advance it and more of a focus on side quests. I see no reason why a sandbox game couldn’t have an even more complicated story structure with branching or threaded paths, other than the sheer amount of content involved in the story writing.

February 9, 2010 at 6:27 am

but with sandbox games giving the player the ability to ignore the story wouldnt the storytelling have less of an impact because you can affect certain aspects of the way the story is paced or retains tension etc?

February 12, 2010 at 4:04 pm

Jason, you’re right that the ability to ignore the story does lessen the focus on such a story. I think that is part of the appeal of the genre, that the player can either follow the story or ignore it as they see fit. That said, this does not mean the story itself can’t be compelling.

In fact, there seems to be a trend even among more story-based games, to allow the player to ignore the story. In Bioshock, for example, most of the story is on these audiotapes that you actually have to push a button to listen to, so you can just play it as a run-and-gun shooter if you want. In World of Warcraft, most of the quests you get have a long backstory behind the quest, and then a summary at the end… so you can either read all this text, or just skip to the bit about collecting 5 rat whiskers and ignore the rest. Ironically, this actually allows the story to become MORE prominent for the players that care about it, because it is their choice to follow the story and not something that is shoved down their respective throats 🙂

In sandbox games in particular, you’re right that one of the challenges is dramatic pacing, because the story writer has no control over how the player experiences the story. I think complex stories with multiple subplots that can all be advanced separately in some kind of open-world RPG (as with Fallout 3 or Oblivion) have similar challenges. I have no real advice here, other than look at games that do this well and games that do it poorly, and try to find the patterns…

September 28, 2011 at 3:42 pm |

[…] dirigé par le Game Designer Ian Schreiber, et plus particulièrement un chapitre consacré à la narration délinéarisée dans les jeux vidéo. A la lecture de ce passionnant article, une constatation s'imposait : ce que Schreiber décrivait […]

October 7, 2011 at 8:54 pm |

In your discussion of how to make interactive stories, you left out the ‘story net’ described in the book, “Chris Crawford on Interactive Storytelling”. There is a lot of good meat in that book on creating drama, the programming of characters with depth which develop depending on how the player acts towards them, and the importance of gossip and secrets in drama.

I highly recommend it. Rick

December 11, 2011 at 12:50 pm |

[…] It is based on Ian Schreiber’s excellent course, Game Design Concepts. Particularly this part. […]