I’m excited about this week, because this is where we’re going to really get into the essence of game design, starting today with decision-making and continuing this Thursday with the nature of fun. These are some of my favorite topics to discuss, because it is the interactivity between players and systems that sets games apart from most other traditional media. This is where the magic of play happens, and as a systems designer, this strikes at the heart of what I deal with when making a game.

Course Announcements

I understand that with 1400+ people, there will be a wide variance in free time. Some of you are students on holiday and can throw yourselves full-bore into this course with all its challenges. Others of you have day jobs and must focus on providing for yourself and your family first. Some of you are going through transitions of a personal nature, such as moving to a new city or dealing with the death of a loved one. This is all understandable, and expected.

So, I would like to clarify my expectations. My expectation is that each of you give what you can to your education. My hope is that you will take out of this course more than you put in. That is all.

If you have a week where you can do no more than read the blog, then that is what you should do. Obviously you will learn more if you do the challenges, but if you can’t, better to do something than to drop everything. This course does not have to be an all-or-nothing venture, and I never intended it to be that way.

If you must prioritize, I would suggest the following:

- First, read the blog. This is the cornerstone of everything else in the course, so if you can do nothing else, do this. This includes the readings referenced in the blog from other sources. (If you fall behind, then hopefully you can catch up on the reading later. I will leave this blog online after the course is finished.)

- If you have some extra time after that, but not enough to do everything, please provide feedback and peer review to your fellow participants on the forums, in the Project Postings section. I think the people that take the time to do the challenge and post it deserve to have feedback, and time constraints prevent me from giving it myself, so this must be participant-driven and grass-roots in nature. As a courtesy to others, do this if you possibly can.

- If you have all the time you need, do the challenge and post it.

Mini-Challenge Results

Here are a small selection of the answers to the mini-challenge from last time (propose a concept for an art game):

- A game where players have a secret goal and try to guess other players’ goals, as a metaphor for growing up gay.

- A game similar to The Sims, except it becomes harder to perform functions as time progresses, to get across the feeling of being afflicted with Alzheimer’s.

- A first-person shooter where players are only shown a single line showing the player’s line-of-sight, showing the view of a 2D hero in a Flatland world.

- A sorcery-themed game where the effects of spells are designed during play.

Readings

Read the following:

- Challenges for Game Designers, Chapters 5 and 6 (Chance / Strategic Skill)

- A Theory of Fun for Game Design, Chapters 1, 2 and 3 (Why Write This Book / How the Brain Works / What Games Are)… if you chose to acquire this book. In an earlier comment, someone suggested only reading the cartoons on each page first, then going back and reading the text afterward.

- Building a Princess Saving App (PDF), by Dan Cook. This article is actually written for an audience of interaction designers to explain what productivity applications can learn from games. In the process, though, it also happens to touch on some core concepts of game design and the nature of “fun” which is exactly what we’re talking about today.

Decisions

As Costikyan pointed out in I Have No Words, we often use the buzzword “interactivity” when describing games when we actually mean “decision-making.” Decisions are, in essence, what players do in a game. Remove all decisions and you have a movie or some other linear activity, not a game. As pointed out in Challenges, there are two important exceptions, games which have no decisions at all: some children’s games and some gambling games. For gambling games, it makes sense that a lack of decisions is tolerable. The “fun” of the game comes from the thrill of possibly winning or losing large sums of money; remove that aspect and most gambling games that lack decisions suddenly lose their charm. At home when playing only for chips, you’re going to play games like Blackjack or Poker that have real decisions in them; you are probably not going to play Craps or a slot machine without money being involved.

You might wonder, what is it about children’s games that allow them to be completely devoid of decisions? We’ll get to that in a bit.

Other than those two exceptions, most games have some manner of decision-making, and it is here that a game can be made more or less interesting. Sid Meier has been quoted as saying that a good game is a series of interesting decisions (or something like that), and there is some truth there. But what makes a decision “interesting”? Battleship is a game that has plenty of decisions but is not particularly interesting for most adults; why not? What makes the decisions in Settlers of Catan more interesting than Monopoly? Most importantly, how can you design your own games to have decisions that are actually compelling?

Things Not To Do

Before describing good kinds of decisions, it is worth explaining some common kinds of uninteresting decisions commonly found in games. Note that the terminology here (obvious, meaningless, blind) is my own, and is not “official” game industry jargon. At least not yet.

- Meaningless decisions are perhaps the worst kind: there is a choice to be made, but it has no effect on gameplay. If you can play either of two cards but both cards are identical, that’s not really much of a choice.

- Obvious decisions at least have an effect on the game, but there is clearly one right answer, so it’s not really much of a choice. Most of the time, the number of dice to roll in the board game RISK falls into this category; if you are attacking with 3 or more armies, you have a “decision” of whether to roll 1, 2, or 3 dice… but your odds are better rolling all 3, so it’s not much of a decision except in very special cases. A more subtle example would be a game like Trivial Pursuit. Each turn you are given a trivia question, and if you know the correct answer it could be said that you have a decision: say the right answer, or not. Except that there’s never any reason to not say the right answer if you know it. The fun of the game comes from showing off your mastery of trivia, not from making any brilliant strategic maneuvers. This is also, I think, why quiz shows like Jeopardy! are more fun to watch than to play.

- Blind decisions have an effect on the game, and the answer is not obvious, but there is now an additional problem: the players do not have sufficient knowledge on which to make the decision, so it is essentially random. Playing Rock-Paper-Scissors against a truly random opponent falls into this category; your choice affects the outcome of the game, but you have no way of knowing what to choose.

These kinds of decisions are, by and large, not much fun. They are not particularly interesting. All three represent a waste of a player’s time. Meaningless decisions could be eliminated, obvious decisions could be automated, and blind decisions could be randomized without affecting the outcome of the game at all.

In this context, it is suddenly easy to see why so many games are not particularly compelling.

Consider the trivia game that popularized the genre, Trivial Pursuit. First you roll a die, and move in any direction, so which location you land on is a decision. Only a few spaces on the board help you towards your victory condition, so if you can land on one of those it is an obvious decision. If you can’t, your choice generally amounts to which category you’re strongest at, which is again obvious (or blind, to the extent that you don’t know what question you would get in each category until after you choose). Once you finish moving, you’re asked a trivia question. If you don’t know the answer, there is no decision to be made. If you do know the answer, there is a decision of whether to say it or not… but there is no reason not to, so again it is an obvious decision.

Or consider the board game Battleship which seems to keep coming up in our discussions. Just about every decision made in this game is blind. You are given no information on which to base your decision of what space to fire at. Once you hit an enemy ship you do have some information, but you still don’t know which direction the ship is oriented (horizontally or vertically) or where its endpoints are, so the decision is more constrained but not any less blind.

Or consider Tic-Tac-Toe, which has interesting strategic decisions until you reach the age where you master it and realize the way to always win or draw, at which point the decisions become obvious.

What Makes Good Decisions?

Now that we know what makes weak decisions, the easiest answer is “don’t do that!” But we can take it a little further. Generally, interesting decisions involve some kind of tradeoff. That is, you are giving up one thing in exchange for another. These can take many different forms. Here are a few examples (again I use my own invented terminology here):

- Resource trades. You give one thing up in exchange for another, where both are valuable. Which is more valuable? This is a value judgment, and the player’s ability to correctly judge or anticipate value is what determines the game’s outcome.

- Risk versus reward. One choice is safe. The other choice has a potentially greater payoff, but also a higher risk of failure. Whether you choose safe or dangerous depends partly on how desperate a position you’re in, and partly on your analysis of just how safe or dangerous it is. The outcome is determined by your choice, plus a little luck… but over a sufficient number of choices, the luck can even out and the more skillful player will generally win. (Corollary: if you want more luck in your game, reduce the total number of decisions.)

- Choice of actions. You have several potential things you can do, but you can’t do them all. The player must choose the actions that they feel are the most important at the time.

- Short term versus long term. You can have something right now, or something better later on. The player must balance immediate needs against long-term goals.

- Social information. In games where bluffing, deal-making and backstabbing are allowed, players must choose between playing honestly or dishonestly. Dishonesty may let you come out better on the current deal, but may make other players less likely to deal with you in the future. In the right (or wrong) game, backstabbing your opponents may have very negative real-world consequences.

- Dilemmas. You must give up one of several things. Which one can you most afford to lose?

Notice the common thread here. All of these decisions involve the player judging the value of something, where values are shifting, not always certain, and not obvious.

The next time you play a game that you really like, think about what kinds of decisions you are making. If you have a particular game that you strongly dislike, think about the decisions being made there, too. You may find something about yourself, in terms of the kinds of decisions that you enjoy making.

What About Action Games?

At this point, the video gamers among you are wondering how any of this applies to the latest First-Person Shooter. After all, you’re not exactly strategizing about resource management tradeoffs in the middle of a heated battle where bullets and explosions are flying all around you.

The short answer here is that you are making interesting decisions in such games, and in fact you are making them at a much faster rate than normal – often several meaningful decisions per second. To compensate for the intense time pressure, the decisions tend to be much simpler: fire or dodge? Aim or move? Duck or jump?

Time limits can, in fact, be used to turn an obvious decision into a meaningful one. Another way I prefer to say this is that time pressure makes us stupid. For a more thorough discussion of action games and how skill relates to them, see Chapter 7 (Twitch Skill) in Challenges for Game Designers.

Emotional Decisions

There is one class of decisions that is useful to consider: decisions that have an emotional impact on the player. The decision of whether to save your buddy (while using some of your precious supplies) or leave him behind to die (potentially denying yourself some AI-assisted help later on) in Far Cry is a resource decision, but it is also meant to be an emotional one – and certainly, an identical decision made on a real-life battlefield would come down to more than just an analysis of available resources and probabilities. Likewise, the majority of players do not play through a game with moral choices (such as Knights of the Old Republic or Fable) as pure evil – not because “evil” is a suboptimal strategy, but because even in a fictional simulated world, a lot of people can’t stomach the thought of torturing and killing innocent bystanders.

Or consider a common decision made at the start of many board games: what color are you? Color is usually just a way to uniquely identify player tokens on the board, and has no effect on gameplay. However, many people have a favorite color that they always play, and can become quite emotionally attached to “their” color. It can be rather entertaining when two players who “always” play Green, play together for the first time and start arguing over who gets to be Green. If player color has no effect on gameplay, it is a meaningless decision. It should therefore be uninteresting, and yet some players paradoxically find it quite meaningful. The reason is that they are emotionally invested in the outcome. This is not to say that you can cover up a bad game by artificially adding emotions; but rather, as a designer, be aware of what decisions your players seem to respond to on an emotional level.

Flow theory

Let’s talk a little bit about this elusive concept of “fun.” Games, we are told, are supposed to be fun. The role of a game designer is, in most cases, to take a game and make it fun. I’ve used the word “fun” a lot in this course without really defining it, and it has understandably made some of you uncomfortable. Notice I usually enclose the word “fun” in quotation marks, on purpose. My reasoning is that “fun” is not a particularly useful word for game designers. We instinctively know what it means, sure, but the word tells us nothing about how to create fun. What is fun? Where does it come from? What makes games fun in the first place? We will continue to talk about this on Thursday, but I want to start talking about it now. I’m sure you can agree it has been long enough.

Interesting decisions seem like they might be fun. Is that all there is to it? Not entirely, because it doesn’t say anything about why these kinds of decisions are fun. Or why uninteresting decisions are still fun for children. For this, we turn to Raph Koster.

What a lot of Koster’s Theory of Fun boils down to is this: the fun of games comes from skill mastery. This is a pretty radical statement, because it equates “fun” with “learning”… and at least when I was growing up, we were all accustomed to regard “learning” with “school” which was about as not fun as you could get. So it deserves a little explanation.

Theory of Fun draws heavily on the work of psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (pronounced just like it’s spelled, in case you’re wondering), who studied what he called the mental state of “flow” (we sometimes call it being “in the flow” or “in the zone”). This is a state of extreme focus of attention, where you tune out everything except the task you’re concentrating on, you become highly productive, and your brain gives you a shot of neurochemicals that is pleasurable – being in a flow state is literally a natural high.

Csikszentmihalyi identified three requirements for a flow state to exist:

- You must be performing a challenging activity that requires skill.

- The activity must provide clear goals and feedback.

- The outcome is uncertain but can be influenced by your actions. (Csikszentmihalyi calls this the “paradox of control”: you are in control of your actions which gives you indirect control over the outcome, but you do not have direct control over the outcome.)

If you think about it, these requirements make sense. Why would your brain need to enter a flow state to begin with, blocking out all extraneous stimuli and hyper-focusing your attention on one activity? It would only do this if it needs to in order to succeed at the task. What conditions would there have to be for a flow state to make the difference between success and failure? See above – you’d need to be able to influence the activity through your skill towards a known goal.

Csikszentmihalyi also gave five effects of being in a flow state:

- A merging of action and awareness: spontaneous, automatic action/reaction. In other words, you go on autopilot, doing things without thinking about them. (In fact, your brain is moving faster than the speed of thought – think of a time when you played a game like Tetris and got into a flow state, and then at some point it occurred to you that you were doing really well, and then you wondered how you could keep up with the blocks falling so fast, and as soon as you started to think about it the blocks were moving too fast and you lost. Or maybe that’s just me.)

- Concentration on immediate tasks: complete focus, without any mind-wandering. You are not thinking about long-term tradeoffs or other tasks; your mind is in the here-and-now, because it has to be.

- Loss of awareness of self, loss of ego. When you are in a flow state, you become one with your surroundings (in a Zen way, I suppose).

- There is a distorted sense of time. Strangely, this can go both ways. In some cases, such as my Tetris example, time can seem to slow down and things seem to happen in slow motion. (Actually, what is happening is that your brain is acting so efficiently that it is working faster; everything else is still going at the same speed, but you are seeing things from your own point of reference.) Other times, time can seem to speed up; a common example is sitting down to play a game for “just five minutes”… and then six hours later, suddenly becoming aware that you burned away your whole evening.

- The experience of the activity is an end in itself; it is done for its own sake and not for an external reward. Again, this feeds into the whole “here-and-now” thing, as you are not in a mental state where you can think that far ahead.

I find it ironic, when a typical kid is in their “not now, I’m playing a game” mental state, the parent complains that they are “zoned out.” In fact, the gamer is in a flow state, and they are “zoned in” to the game.

Flow States in Games

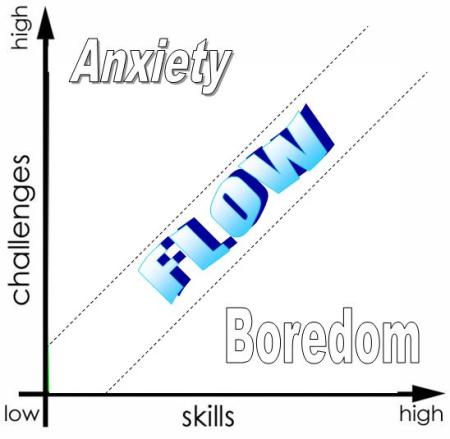

Simplifying this a bit, we know that to be in a flow state, an activity must be challenging. If it is too easy, then the brain has no reason to waste extraneous mental cycles, as a positive outcome is already assured. If it is too difficult, the brain still has no reason to try hard, because it knows it’s just going to fail anyway. The goal is to hit that sweet spot where the player can succeed… but only if they try hard. You’ll often see a graph that looks like this, to demonstrate:

All this says is that if you have a high skill level and are given an easy task, you’re bored; if you have a low skill level and are given a difficult task, you’re frustrated; but if the challenge level of an activity is comparable to your current skill level… flow state! And this is good for games, because this is where a lot of the fun of games comes from.

Note that “flow” and “fun” are not synonyms, although they are related. You can be in a flow state without playing a game (and in fact without having fun). For example, an office worker might get into a flow state while filling out a series of forms. They may be operating at the edge of their ability in filling out the forms as efficiently as possible, but there may not be any real learning going on, and the process may not be fun, merely meditative. (Thanks to Raph for clarifying this for me.)

One Slight Problem

When you are faced with a challenging task, you get better at it. It’s fun because you are learning, remember? So, most people start out with an activity (like a game) with a low skill level, and if the game provides easy tasks, then so far so good. But what happens when the player gains some competency? If they keep getting the same easy tasks, the game becomes boring. This is essentially what happens in Tic-Tac-Toe when a child makes the transition to understanding the strategy of the game.

By the way, we can now answer our earlier question: why can children’s games get away with a lack of meaningful decision-making? The answer is that young children are still learning valuable skills from these games: how to roll a die, move a token on a board, spin a spinner, take turns, read and follow rules, determine when the game ends and who wins, and so on. These skills are not instinctive and must be taught and learned through repeated play. When the child masters these skills, that is about the time when decision-less games stop holding any lasting appeal.

Ideally, as a game designer, you would like your game to have slightly more lasting playability than Tic-Tac-Toe. What can you do? Games offer a number of solutions. Among them:

- Increasing difficulty as the game progresses (we sometimes call this the “pacing” of a game). As the player gets better, they get access to more difficult levels or areas in a game. This is common with level-based video games.

- Difficulty levels or handicaps, where better players can choose to face more difficult challenges.

- Dynamic difficulty adjustment (“DDA”), a special kind of negative feedback loop where the game adjusts its difficulty during play based on the performance of the player.

- Human opponents as opposition. Sure, you can get better at the game… but if your opponent is also getting better, the game can still remain challenging if it has sufficient depth. (This can fail if the skill levels of different players fall out of synch with one another. I like to play games with my wife, and we usually both start out at about the same skill level with any new game that really fascinates us both… but then sometimes, one of us will play the game a lot and become so much better than the other, that the game is effectively ruined for us. It is no longer a challenge.)

- Player-created expert challenges, such as new levels made by players using level-creation tools.

- Multiple layers of understanding (the whole “minute to learn, lifetime to master” thing that so many strategy games strive for). You can learn Chess in minutes, as there are only six different pieces… but then once you master that, you start to learn about which pieces are the most powerful and useful in different situations, and then you start to see the relationship between pieces, time, and area control, and then you can study book openings and famous games, and so on down the rabbit hole.

- Jenova Chen’s flOw provides a novel solution to this: allow the player to change the difficulty level while playing based on their actions. Are you bored? Dive down a few levels and the action will pick up pretty fast. Are you overwhelmed? Run back to the earlier, easier levels (or the game will kick you back on its own if needed).

You’ll notice that when we read in a review that a game has “replayability” or “many hours of gameplay” what we are often really saying is that the game is particularly good at keeping us in the flow state by adjusting its difficulty level to continue to challenge us as we get better.

Why Games?

You might wonder, if flow states are so pleasurable and they are where this elusive and mysterious “fun” comes from, why do we design games to do this and not some other medium? Why not design productive tasks to induce flow states, for example, so that maybe we could get a few million people working on discovering a cure for cancer instead of playing World of Warcraft? Why not design college classes to induce flow states, so that a student could learn a typical 50-hour class in a week (the same way they might play through a 50-hour RPG on their PlayStation) instead of having that same class take an entire 10 or 15 weeks?

Games just happen to be naturally good at putting players in a flow state, so it is much easier to design a fun game than a fun course in Calculus. As Koster points out in A Theory of Fun, the brain is a great pattern-matching machine, and it is the finding and understanding of patterns that is what is happening when our brain is in a flow state. I think games bring this out really well because you have three levels of patterns: feeling the Aesthetics, discerning the Dynamics, and finally mastering the Mechanics (in the MDA sense). Since every game has these three layers of patterns, games are three times as interesting as most other activities.

“Edutainment” Games

You might think that, if games are so great at teaching and if learning is so darned pleasurable, that educational games would be more fun than anything. In reality, of course, “Edutainment” is a dirty word that we only mention when forced, as the vast majority of games that bill themselves as “fun… and educational!” are actually neither. What’s going on here?

Many “Edutainment” games work like this: first you’ve got this game, and you play it, and it’s maybe kind of fun. And then the game stops, and tries to give you some kind of gross, icky, disgusting learning. And as a reward for doing the learning, you get to play the game again. Gameplay is framed as a reward for the inherently unpleasurable task of learning something. We have a name for this: chocolate-covered broccoli.

I think this design contains an error of thinking, and this infects the design of such games at a fundamental level, invalidating the whole premise. The error is the separation of “learning” and “fun” because, as you now know, these are not separate concepts but rather identical (or at least strongly related). The assumption that learning is not fun and that fun cannot be inherently educational undermines the entire game… and incidentally, also reinforces the extremely damaging notion that education is a chore and not a pleasure.

It would be wonderful if we could stop teaching that “learning is not fun” lesson to our children. It would certainly make my life a lot easier as a teacher, if I did not have to first convince my students that they should be intrinsically motivated to do well in my classes.

What if you want to design a game that has the primary purpose of teaching, then? That is a subject that deserves a course of its own. My short answer: start by isolating the inherently fun aspects of learning the skills you want to teach, and then use those as your core mechanics. By integrating the learning and the gameplay (rather than keeping them as separate concepts or activities), you take a large step towards something truly worthy of the “fun, and educational” label.

A Note for Teachers

If you’ve accepted everything in this lesson so far, you might see a parallel with teaching. If learning is inherently fun, think about what you can do to draw that out of your subject.

- How many interesting decisions do your students make? I once saw a statistic that the average college student raises their hand in class once every ten weeks – that’s three meaningful decisions per year! Can you do better? Consider giving a choice of assignments (with built-in tradeoffs: for example, an easy-but-boring homework or a difficult-but-interesting one). Ask lots of questions in class that get students involved. Have class discussions or debates.

- Are too many of your students bored or overwhelmed, because your class is at a difficulty that is too low or too high? Games have this problem too, and often solve it through including multiple difficulty levels; consider having a tiered grading system where remedial students should be able to pass if they can at least put in the work to grasp the basics, while offering advanced students extra work that is more interesting. Offer the course content in layers, first going over the very basics in a “For Dummies” way that everyone can get, then add the main details that are really important, and finally give some advanced applications that only some students might understand, but that are interesting enough that students will at least have some incentive to reach a bit.

- The most fun games are designed in a player-centric manner, concentrating first on providing a quality experience. You can tell a game where the designer made a game that they wanted to play, because it sold a total of five copies to the designer, the designer’s close friends, and the designer’s mom. You can also tell a game where the designer started with content rather than gameplay; these are the games that have deep, involving stories and incredible layers of content, but no one sees them because the gameplay is boring and people stop playing after five minutes. What would your class be like if you start your lesson plans by thinking of the student experience, rather than designing a class that you find interesting (your students might not share your research interests), or designing a class based around content (which is probably not engaging until you bring it to life)?

Lessons Learned

Decisions are the core of what a game is. When critically analyzing a game (yours or someone else’s), pay attention to what decisions the players are making, how meaningful those decisions are, and why. The more you understand about what makes some decisions more compelling than others, the better a game designer you are likely to be.

Games are unnaturally good at teaching new skills to players. (Whether those skills are useful or not, varies from game to game.) Learning a new skill – by being given a challenge that forces you to try hard and increase your skill level – is one of the prerequisites for putting players in a flow state. Flow states are an intensely pleasurable state for the brain to be in, and a lot of the feeling of “fun” that comes from playing games comes from being in the flow.

There it is! Mystery solved! You now know everything there is to know about where “fun” comes from and how to create it. Okay, not really. But this is a start, and we will probe a bit deeper into the nature of “fun” this Thursday.

Feedback

If you have time, before beginning the Homeplay below, please take the time to offer constructive feedback to at least three other posts from the art games from Level 6 (posted on the forum). If you posted a game yourself, offer feedback to other posts in the same category as you posted yours. If you were unable to post a game last time, then choose whichever of the four topics most interests you (see the bottom of Level 6 for details).

Try to complete your feedback on or before Thursday, July 23, noon GMT.

Homeplay

This time around, let’s practice our ability to provide meaningful decision-making to players. We are going to make a mod of a game. (This homeplay is adapted from Challenge 6-1 in the Challenges text.)

Here are the basic rules for the children’s card game War:

- Players: 2

- Materials: one standard 52-card deck of playing cards (with Jokers removed)

- Setup: Shuffle the deck of cards and deal out half to each player. Players take their cards in a single face-down stack.

- Progression of Play: Simultaneously, players flip over the top card of their deck. If the cards are of unequal rank (number), the higher rank wins the “battle” and that player takes both cards and sets them aside in a discard pile (Aces are high, then King, Queen, Jack, then 10 down to 2). When a player runs out of cards in their deck, they take their discard pile and turn it over to form a new deck.

- Wars: If players flip over cards that are equal rank, it starts a “war.” Players each deal three cards face-down, then flip up a new card face-up, and the higher rank of the new face-up card wins all face-down and face-up cards. This process is repeated if the new face-up cards are the same rank, continuing with additional “wars” until eventually one player wins.

- Resolution: The game ends when one player runs out of cards, or when one player must play cards for a “war” but they do not have enough cards remaining in their deck and discard pile. That player loses the game, and their opponent wins.

This game has no decisions whatsoever. The game mechanically plays itself, and the players merely act as tools to play out the game to its pre-determined conclusion.

Change the rules so that the game outcome is determined primarily by skill, and that the game now has interesting, meaningful decisions.

Post in the forum that most closely resembles your skill and experience level as a designer:

Beginner, little or no experience prior to taking this course.

Beginner, little or no experience prior to taking this course.

Intermediate, some coursework or exposure to game design but little or no professional experience.

Intermediate, some coursework or exposure to game design but little or no professional experience.

Advanced, at least some professional experience as a published game designer.

Advanced, at least some professional experience as a published game designer.

Make your post on or before Thursday, July 23, noon GMT. Then, offer constructive feedback to at least two other posts in the same forum, and at least three posts in one forum “below” yours if you posted in Blue Square or Black Diamond.

Mini-Challenge

Add a rule that gives interesting decisions to Trivial Pursuit that can be expressed in 135 characters or less. Post it to Twitter with the #GDCU tag. One rule change per person, please! Tweet before July 23, noon GMT.

Parting Shot

If you’re still curious, “Csikszentmihalyi” is pronounced “Chick-sent-me-high”. Seriously, I’m not making this up. It’s not exact, but it’s about as close as you can get with an English-language transliteration.

July 20, 2009 at 7:29 am |

I apologize for not following the course as I should. I am trying as hard as I can to translate it in italian, but this (coupled with my everyday life) slows me down incredibly. I am still translating lesson 5… 😦

I will devote myself more to the challenges from now on!

By the way, I was thinking… what’s the point of translating the course in italian? I see there’s little more than 3 italians following the course, I know the wiki is public but I don’t think there’s an “only-italian-speaking-game-designer” that is really interested in it. What a shame.

July 20, 2009 at 7:34 am |

And because of this, do you think there’s a point in translating the course in italian AFTER it has ended in english? Because it is unavoidable (does “unavoidable” exist? :D)

July 20, 2009 at 10:36 am |

This course will remain online after it is finished, so if an Italian-only speaker does manage to find it after the fact, I’m sure a translation would be useful.

Also, don’t just go by the numbers in the forums. A lot of people only found out about this after it had already started (or just decided to read the blog but not participate in the forums/wiki), and are following along silently. I have no idea where those other people are from — could be anywhere.

July 20, 2009 at 10:42 am

I posted the link to the italian translation on an italian forum dedicated to game development and, ammittedly, very few people have answered…

http://www.aiomi.it/forum/viewtopic.php?f=27&t=114

But again, as you say, maybe in the future someone will find the course on its own and read it later. So I’ll go on, maybe only a little slower..

July 20, 2009 at 8:11 am |

I managed to do the very first challenge in the book (one of the ones you later specified that we didn’t even need to do) but have since been swamped with work and family life. It’s driving me absolutely crazy that I can’t devote more to this class that I was so looking forward to. I’ll try to make some time for feedback in the forums at the very least.

July 20, 2009 at 9:23 am |

FYI:

Csíkszentmihályi (notice that the second letter is “s”, not “z”) is pronounced “cheek-sent-me-high-e” with a short “me” in the middle and “e” at the end. I notice you must have heard this before, but I must reiterate that it’s pronounced exactly as it’s spelled. 🙂

July 21, 2009 at 9:18 am |

Whoops. I’m usually more careful about my spelling than this. Post has been fixed.

Your pronunciation is more accurate, but note that it requires an extra text explanation afterward. I try to keep things simple, and I figure anyone who is advanced enough in the field to need to know a 100% correct pronunciation probably knows it already 🙂

July 20, 2009 at 10:24 am |

This is admittedly a bit nit picky, but I disagree with the assessment that War has no decisions. I think it has 1 mostly blind decision: the order that you place the cards in your discard pile. The posted rules do not govern this order, and it can turn out to be very important. Perhaps your ace, instead of your queen, will now come up when your opponent’s king does.

July 20, 2009 at 10:37 am |

That is a good point. I suppose a sufficiently skilled player could re-order their cards optimally in this fashion. When I played, I do not remember doing this consciously, the cards were just added in random order.

July 20, 2009 at 10:39 am |

@MrCactus:

It’s right that the posted rules don’t say where you should put the discarded cards, but I think that if a player tried to put one below the deck, this would cause an argument.

I think that placing discarded cards above the deck is one of those implied rules mentioned earlier in the course.

Anyway even if it was like you said, placing a card where you wanted is not going to be a ‘decision’, because you don’t know which card the opponent will draw, and moreover the opponent isn’t going to draw the card he wants, so it’s pointless to devise a strategy against someone who is playing randomly, isn’t it?

July 20, 2009 at 12:34 pm

I feel that I must clarify/disagree.

I meant ordering the cards in the discard pile for a single play. If my 10 beats your 7, the rules don’t say which card goes onto the discard pile first.

The whole issue could be made moot by shuffling the cards in the discard before using them.

Deciding which order you put the cards into your discard is a decision. Unless you have an astounding memory, it’s a blind one, but a decision nonetheless. It can have a big effect on the game ass well. That makes it meaningful too, even if the player is not aware of the effects of it, or even that they made a decision at all.

July 20, 2009 at 6:08 pm |

Ian,

Thanks for the understanding that not everyone can do every assignment.

I am learning and getting a lot out of this course and have worked my studies into my game design projects. I had such a good response on the WWI project I am going to be releasing it in a few weeks through GameCrafter after some vigorous testplaying.

I think many many people are getting a lot out of this relevant and professionally delivered course.

– Del Esau

July 20, 2009 at 7:25 pm |

I have been following the course since the beginning. One thing I am puzzled by: up till now, you never mentioned the BRIDGE game, which I consider one of the most challenging (and fun) ever! By the way, my own TimeShex (R) GAME Project has some remnants of Bridge strategy (together with a mixture of World of Warcraft). I am an avid Bridge player, and it is indeed the “Chess” of the card games. I focus on pure creativity, something we do not find these days (everything is repetitive of a similar idea, all violently based on “kill, destroy, conquer”). I personally consider MONOPOLY when it reached us in the 60s in the Middle East as very creative indeed. I did start a Facebook topic about CREATIVITY IN GAME DESIGN, and am regularly in touch with Dustin Clingman (head of IGDA Orlando, FL chapter), Jason Della Rocca, Noah Falstein, Greg Costikyan, Phil Orbanes (Monopoly) and Raph Koster. Don’t you think that we do have a major creativity crisis in videogames in general?

July 20, 2009 at 9:50 pm |

game name: Humanitarian Aid

*objective: To earn the most humanitarian stars and become the #1 humanitarian

*players: 4

*materials: one standard 52-card deck of playing cards (with Jokers removed) for each player

*setup: on the first turn, each player draws 7 cards

*game progression:

1 Draw phase – each turn after the first, going counter-clockwise, each player draws 3 card

2 Switch phase – players may put any card at the bottom of their deck, and draw another, one per turn

3 Placement phase – black cards represent wounded soliders, players take turns placing up to 3 solider cards on the hospital bed (table)

4 Healing phase – red cards represent nurses, players take turns healing the soliders w/ up to 3 nurse cards (only soldiers that are not yours)

-how healings works: number (or picture) of nurse card matches number (or picture) of solider card

-note: The number on the card represents the number of soliders, for black cards, or nurses, for red cards

5 Reward phase – humanitarian star: each match earns 2 humanitarian star for the player who did the healing, and 1 humanitarian star for the player being healed. Bonus for cards matched w/ pictures (queen, king, jack), 4/2 instead of 2/1

6 Ending phase – both solider and nurse cards are placed at the bottom of their respective decks

*winning conditions: The players set the max stars, and when that is reach, you found the #1 humanitarian. Everyone is considered a winner =D

posted on http://iambinary.weebly.com/

unfortunately, i can’t help on the forums cos it’s inaccessible.

how can the design be improved?

how am i as a game designer?

July 22, 2009 at 12:37 am |

i need feedback and help ppl! =D

how can the design be improved?

how am i as a game designer?

July 23, 2009 at 5:44 pm

Critical Analysis: Humanitarian Aid

(1) Formal Elements/Mechanics/Game Structure

(A) Player(s)

* Type of Relationship – Cooperative free-for-all

* Number – Says 4 but after playing it we’d say 3 or more – can image 8 players playing without any problems

(B) Objectives (goals)

* General – Build/matching

* Specific – Earn most points by “healing the most soldiers”

(C) Rules

* Operational – Easy to follow as stated; playable as is.

* Constituative (underlying systems) – Matching game

* Implied (unwritten social contract) – This has the feel of a cooperative game, but unsure what implied rules might be there.

(D) Resources

* What Kinds – Nurses and soldiers

* How Manipulated – Match to other players cards

(E) Game View – This game begs to be played cooperatively; so although the rules don’t specify this, playing with cards face up or showing another player your hand allows players to cooperate to an even greater degree.

(2) Formal Elements in Motion/Dynamics/Craft

(A) Interaction of Elements – Each turn generates excitement in terms of making as many matches as you can. Also, which soldiers are available to be healed changes with each turn, so the potential matches are in a state of constant flux. This keeps the gameplay “fresh”.

(B) Types of Decisions – Mostly blind and obvious decisions – you play the black cards you have without knowing if anyone will be able to match, or in the case of a nurse card, if you can play it, you do. Switch phase adds somewhat more of a meaningful decision in determining whether to utilize it or not. One other type of decision that comes up, is when you have a nurse card that can be played on more than one other player, you must decide which player to heal. This can be a meaningful decision if the players are focusing on points, and one of them is further ahead… This is a fun game for 10 and under, and the level of complexity of the decisions is appropriate to that age range.

(C) Effectiveness – The game is quite effective – the gameplay fits in with the theme of “humanitarian aid” quite well – it rewards cooperation and “everyone wins”. As expected, it’s not a game of bloodthirsty competitiveness, but it does have a touch of competition – “be the best nurse.”

(3) Player Experience/Aesthetics/Surface

(A) Players affect each other – Since both the “healer” and the “healed” get points, the effect the players have on each other is a positive one. Even with the point system, the overall feeling of the game is mutually helping each other so everyone wins.

(B) Perceived by the players as fair – yes

(C) Replayable – Yes, similar to “Solitaire” but has slightly more replay value due to narrative/story line.

(D) Intended Audience – From playing it we think the game is ideally suited for ages 4 – 10.

(E) “Core”/“Fun” Part – “Healing” is fun; you get the twin thrills of achievement (matching cards) and victory (getting points)

(4) Comments:

Our 7 year old daughter really enjoyed this game because it appealed to her desire to help as well as her desire to win. This game does seem to balance these 2 desires fairly well particularly for younger players – nice job!

(5) Suggestions:

* Instead of a pure turn-based game use a mix of simultaneous and turn-based play:

Actions players are able take anytime:

– Keep your “hospital beds” full at all times

– Keep your hand at 7 cards at all times

Actions players are able take only during their turn:

– Switch Phase

– Healing & Reward Phases

July 20, 2009 at 10:22 pm |

From “Challenges for game designers”, “meaningless decisions”: “Doest thou wish to see the king” – While the answer is meaningless in terms of changing the game state it does offer self-expression so I would disagree that it is entirely meaningless. I know bordering on being pedantic here but thought I’d mention it anyway.

“”official” game industry jargon”, that one made me laugh

Best fonts I’ve seen yet in a “Flow” diagram 😉

July 21, 2009 at 3:15 am |

In the subject of educational games, over at TIGSource there’s currently a competition for educational (also adult) games:

http://forums.tigsource.com/index.php?topic=6883.0

July 21, 2009 at 7:31 am |

Czikszentmihalyi is pronounced aprrox. the way you did, but with a very short “e” at the end:))

July 21, 2009 at 7:34 am |

ok, I just saw that I’m not the only Hungarian here:)

July 21, 2009 at 11:19 am |

Best lesson yet IMO. I really enjoyed reading through Level 7.

July 21, 2009 at 12:00 pm |

It’s funny how the educational games topic surprising worked is way into Flow and Decision making.

I agree with the concepts discussed so far. I think that one of the main problems with educational games may be that they can be too specific or too devoid of context.

Take language. You could offer a game like any other adventure game where the player is spoken to in a different language therefore offer a sort of virtual immersion. Armed with a system for looking up learned words a compelling point and click mystery could be created.

Here are some samples of other games that I find to be quite engaging.

* Questionaut -By Amirita, mixes point and click with simple multiple choice questions on a variety of school subjects. http://www.bbc.co.uk/schools/ks2bitesize/games/questionaut/

* Globe Trotter XL – The game calls out a city and you click it on the map. God knows how something that sounds so boring can be so much fun. http://www.kongregate.com/games/crafics/globetrotter-xl

* Path Ways 2 – This is a math game. You are given a additive or subtractive rule (ex. + 1 and -2) and you try to plot out a path through a grid of numbers to the goal. Very easy and yet very hard at the same time. http://www.kongregate.com/games/Startdl/pathways-2

* 1066 – Is a turn based strategy game in which Vikings, Welsh and English fight infantry battles over control of Britain. It set in 1066 England and is based on a TV show. Turn based strategy of historic battles that are pleasing to play and pleasing to the eye. http://www.channel4.com/history/microsites/0-9/1066/game/index.html

* Red Herring Chase – It’s a top down game where you play a classy 1940 lady who has tell the cab driver to follow a case. You do this by typing your instructions. The writing is not just left and right but really good film noir one liners like “Punch it budy”, “hit a right”, etc. Can be a little tricky when it comes to spaces, capitalization and punctuation. http://www.intuitiongames.com/red-herring-chase/

July 21, 2009 at 3:48 pm |

“For gambling games, it makes sense that a lack of decisions is tolerable. The “fun” of the game comes from the thrill of possibly winning or losing large sums of money; remove that aspect and most gambling games that lack decisions suddenly lose their charm.”

There is a decision here that you’re missing; you’re deciding how much money to wager, where, and when. These decisions are easily as complex as most other games, as they depend on each person’s personality and real life finances, in addition to the generally simple constraints given by the game. These decisions also directly impact life outside the game, to some degree, which provides a much stronger feedback loop than other games.

The ability to see yourself as choosing correctly, or even almost correctly, when money is on the line drives the fun of gambling.

July 21, 2009 at 4:57 pm |

Hanged Man: You are correct that choosing how much to bet is (sometimes) a decision. In a case where you are counting cards, it is even a meaningful and skill-based decision (to the point where the casino will boot you out the door when they catch on 🙂 ).

In the case of a purely luck-based game, though, the amount of the wager is a blind decision. Yes, it is a choice, but wagering more money on THIS round of Craps as opposed to a different round is something based purely on luck. Some people will try to “time” their bets, thinking that each throw of the dice is dependent on others (“we haven’t seen a 7 rolled in awhile, it’s about due”) but that is a fallacy, as I’m sure you’re aware.

I would still submit that it is the thrill of gaining or losing money that is where the fun is, and not the choice of the wager amount. Try playing Craps at home, for chips but not for real money. You still have the choice of wager. It’s still not very fun.

July 21, 2009 at 5:25 pm

“In the case of a purely luck-based game, though, the amount of the wager is a blind decision.”

In the case of these games, choosing how much to bet and when lets you control the volatility of the gambling experience and allows the game to be experienced very differently. Look at the difference between a red/black bettor in roulette vs. a straight up number bettor.

I would argue that experience and knowledge of the volatility of a game keeps that decision from being a blind one. You may not know what the outcome will be, but you have a good idea of the experience you’re likely to have (or would like to have, if you’re playing to win a million dollar keno jackpot) over the session, especially in the long term.

July 21, 2009 at 5:33 pm

“I would still submit that it is the thrill of gaining or losing money that is where the fun is, and not the choice of the wager amount. Try playing Craps at home, for chips but not for real money. You still have the choice of wager. It’s still not very fun.”

I realized I wanted to say more. 🙂

I agree with you here: money or its equivalent must be on the line here for these games to give you the rush, fun, or whatever you want to call it. However, I don’t have fun from a $.10 max bet blackjack table so it’s a little more subtle than just money. 🙂

July 21, 2009 at 4:10 pm |

As for games and learning, I must confess that I learned quite a bit of European Geography because of Diplomacy 😉 But apart from that, I think that it is easier to learn skills through games (basically, you’re training them in a game) than knowledges. The game of Diplomacy is quite an inefficient way of spending time if the purpose is to learn geography. OTOH, I remember a computer game, a sort of arcade game where near the left end of the screen was a barrier. From the right, words flowed leftward to that barrier, and you had to type the word before it hit. Good, and effective, typing tutor.

July 21, 2009 at 4:23 pm |

I finished reading the whole thing, and I would like to thank you for making the critique part of the homeplay be about something that we’ve finished. As most people didn’t make the forum posts until the last minute, it’s great to have time to actually consider and play what other people had made.

I wanted to make one last point about gambling games:

“Csikszentmihalyi identified three requirements for a flow state to exist:

* You must be performing a challenging activity that requires skill.

* The activity must provide clear goals and feedback.

* The outcome is uncertain but can be influenced by your actions. (Csikszentmihalyi calls this the “paradox of control”: you are in control of your actions which gives you indirect control over the outcome, but you do not have direct control over the outcome.)”

A slot machine, at first glance, satisfies neither point 1 nor 3, but every regular slot player I know goes into the zone when playing.

3 could be changed to reflect the fact that almost everyone who gambles believes that they have influence over the outcome, even though the machines are designed to give illusory choices.

1 is a bit harder. There are decisions to be made in gambling as I argued above aside from video poker, counting cards, and the like, but when I go into the zone gambling on a slot machine, there is no challenge. My choice of what to bet is made. Something else is at work, and I’m not sure what it is. I know it is about an emotional desire for “action”, i.e. the volatility swings up and down, but I don’t think it comes from seeing self as skillful or matching patterns.

Anyway, interesting work.

July 21, 2009 at 5:10 pm |

This is a great point, and something I plan to address on Thursday. Short version: you can get into flow states in ways other than what was stated in this lesson. Meditation creates a flow-like state through relaxation rather than challenge. Also, maybe you have (or know someone who has) played a video game that they have already beaten many times; clearly no additional learning is going on here, but there is still a flow state.

I welcome any additional thoughts.

July 23, 2009 at 1:29 am |

I like your point. But I also think that gambling is special case of games, the one where game pay-offs translate into real-world pay-off. Therefore, I think the the incentives of a player who plays for gambling, are slightly (or even completely) different from a traditional player who plays for only for “fun”. Since the incentives are different the whole definition of “flow” may also be different for a gambler.

July 21, 2009 at 4:27 pm |

On the topic of educational games, back in high school my economics professor ran a simulation game illustrating the principles of supply and demand (over the course of a few weeks). He divided us into groups of three and we were all competing with each other to earn the most profits. I seem to recall we could control our price and our production. More than a decade later I still remember the lessons I learned through that game, but I don’t have a clue what any one lecture was about.

I’m now wondering how miniature wargaming and role playing could be used in conjunction with history lessons.

July 25, 2009 at 9:49 pm |

Zero Feedback for the “Homeplay” I posted before; that’s disappointing.

July 29, 2009 at 11:43 am |

You didn’t look well enough! Thad Martin gave you a very thorough critical analysis 🙂

November 1, 2009 at 8:15 am |

ah ive been waiting for this lesson. =]

question about moral choice systems. to me, i don’t believe they are based on emotion. they’re more about a trade off between rewards for choosing your path. is this a correct analysis?

November 2, 2009 at 12:34 am |

Great question, Jason.

“question about moral choice systems. to me, i don’t believe they are based on emotion. they’re more about a trade off between rewards for choosing your path. is this a correct analysis?”

I think this depends on both the game and the player.

The video game “Fable” provides a good example here. There are definitely gameplay consequences to the “good” or “evil” path, opening up different skills and abilities. However, Molyneux reported in a GDC 2009 session that only 10% of players finished it as evil. Gameplay-wise, the game is not so terribly unbalanced, so what’s going on here? I think the answer is that the story and the reactions of other characters were convincing enough that many players had an adverse *emotional* reaction to going evil, regardless of potential gameplay advantages.

So it is certainly possible through sufficiently powerful storytelling, to get some players to play suboptimally from a purely ludological perspective 🙂

November 4, 2009 at 9:34 pm

hmm.. well.. for the fable example i would argue that player chose a certain path so they can gain a certain power ups/ weapon etc. now i haven’t played fable but i assume that good and evil have there own unique weapons and power ups. im also guessing that to get the best weapons in the game you have be either 100% good or vice versa. so its not a emotional choice but a reward trade off to suit your playing style.

i agree with your last statement but i dont think a moral choice system is accurate enough to reflect the emotional choices of a player. at least not yet anyways.